The story of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is not a simple one to tell. It involves interaction between complex federal statutes, mountainous administrative wranglings, and frustratingly uncooperative behavior.

As of today though, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has won a significant battle against the continued construction of the pipeline that is backed by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP). However, the Tribe did not do it by winning in court, the Tribe was given a gift by the Army Corps of Engineers who has announced it will not grant a permit for a tiny portion of the pipeline that was due to traverse under the Missouri River, about a half mile to the north of the Tribe’s reservation.

“Although we have had continuing discussion and exchanges of new information with the Standing Rock Sioux and Dakota Access, it’s clear that there’s more work to do,” [Asst. Sect.] Darcy said. “The best way to complete that work responsibly and expeditiously is to explore alternate routes for the pipeline crossing.”

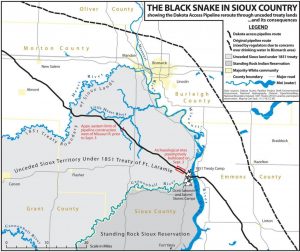

The DAPL has been in the works since 2014. Nearly all of it crosses private land, and because it carries crude oil, and not natural gas, the federal government does not regulate its planning or construction, until the pipeline must cross federally regulated waterways (Clean Water Act and Rivers and Harbors Act). (In this case less than 3% of the pipeline is required to be federally permitted, and less than 1% crosses a waterway.) It is at this crossroads – where the Cannon Ball River and the Missouri River meet in North Dakota that has become the center of the controversy. Though this point is not on a designated Native American reservation, much of the surrounding land has been recognized through other documents (Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851) as having cultural significance to the Sioux Nation. Federal law has accommodated these interests through protective review measures (National Historic Preservation Act) whenever construction will take place on lands under federal jurisdiction.

When ETP began its endeavor to construct the $3.7 billion dollar pipeline, which reaches almost 1,200 miles from Bakkan oil fields in western North Dakota, crosses South Dakota and Iowa, and arrives in southern Illinois, it commenced the permitting process with the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps). This involved identifying relevant sites of federal jurisdiction, providing documentation of plans and surveys of sites of cultural significance. The Corps then involved various other national and local agencies and representatives that include the interested Native American communities. Over the course of the next several months numerous attempts were made to engage with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe – the only one of four other tribes in the area that did not respond to the Corps’ efforts to include them in consultation for the project.

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe was first informed of the project in September 2014 when ETP met with the Tribe and presented the information to the Tribe’s Historic Preservation Officer. Nearly all attempts thereafter to receive input from the Tribe were futile until the Tribe filed its complaint in July 2016. Despite the Tribe either explicitly refusing to participate, or the Tribe simply not responding to requests to engage in the process, the encampment that has been prominent in the news started slowly in April 2016 and since ballooned in the last few months. Various eco-tourists and veterans’ groups have joined the protestors, who call themselves “water protectors,” in an effort to show solidarity against a so-called militarized police force.

Over the summer several protestors (upwards of 140) were arrested (to include actress Shailene Woodley and presidential candidate Jill Stein) after clashes with police. The protestors vandalized and set afire construction equipment on private land. Private security responded with guard dogs and pepper spray. In other incidents where protestors blocked bridges, threw objects at police, and used horses to charge police, police responded with water cannons, pepper spray, rubber bullets, and bean bags. Many of the clashes were caught on cell phone video and portrayed the police as heavy handed and unjustified in their actions.

In the fall of 2016, the Tribe moved for an injunction to halt any permitting by the Corps. It rested its arguments on supposed violations of the National Historic Preservation Act, stating that the Corps had not properly consulted with them in the permitting process. The District Court painstakingly laid out the multitude of attempts the Corps and ETP made to include Standing Rock in the process. The Court also showed that the Corps reasonably came to the conclusions that no cultural sites were in jeopardy, and where they were it was shown that ETP rerouted the pipeline in every circumstance (nearly 200 instances). The Corps and ETP also ensured that the Tribe and other surveying officials were allowed to be present at any site where cultural artifacts might be affected. Through all of the months that the pipeline was being constructed no Tribe representative ever took advantage of the ability to work with ETP or the Corps. The District Court, in a 58 page opinion, decided that the Tribe had not shown that the proper permitting process had not taken place, nor that anything of cultural significance would be harmed anyway.

To add further support for this opinion the Court noted that the specific site where the rivers meet, which is of particular importance to the Tribe, had already been surveyed and approved many years earlier in 1982 for another pipeline and utility easement. The DAPL was planned to route exactly on the same easement, where another pipeline already existed! The DAPL would do nothing to disturb any cultural artifacts in the area and in fact to be extra cautious it would be made of heavy wall pipe to prevent leaks and be even further underground (90 to 115 feet) than was normally proscribed for such construction.

While the news and celebrities have been focusing on the clean water aspects of this case, the Tribe itself did not use that as a basis for its motion for an injunction – it rested its case solely on the potential disturbance of cultural artifacts. The main law suit remains of course in which the concern for pipeline leaks is an underlying issue, but the legal arguments the Tribe has advanced so far – that the permitting process was improper – did not win the day in court. But the encampment and protestors remained and grew and provoked, and won.

The facts that get out to the public are reduced to a few seconds’ sound bite and the full story is not widely known. But what has really happened here is that a private developer envisioned a huge project, secured investors for the project, and set about jumping through all the regulatory hurdles required for this massive undertaking. When the private developer was more than 2/3 of the way complete with the project, interested parties that had been invited to participate from the very beginning finally asserted their disapproval. And despite the developer and the government complying with law in proceeding with the project, the protestor come-latelys who followed no rules of engagement or etiquette have managed to bully their way into getting what they want.

In an open letter, the CEO of Energy Transport Partners notes the Tribe’s concerns are curious given that it has leased its land for crude oil production and allows railways that carry crude oil to cross its lands. The tribes in North Dakota have collectively more than 225 oil wells on their lands which produce 73 million barrels of oil per year resulting in $500 million dollars worth of royalty payments. A final irony is that the chairman leading the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Dave Archambault, owns a gas station.

I don’t have a problem with anyone asserting their desires in a peaceful manner for the use of the land – whether it belongs to them or not. But I do have a problem with the methods and procedures by which we decide such disputes. This project was all but complete, with all the proper legal hurdles satisfied, including winning in court, but one party refused to accept the judicial outcome, until they got what they wanted. They took extra-judicial means to press on, which seems to be the way that most things are working out these days. It no longer matters what should happen according to the predetermined rules.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWKIEge9uxk

Depending on the issue, whether it be siding with the “water protectors,” or siding with ranchers like the Bundys, or any other protestors’ pet causes, at some point we might all agree that taking these matters into your own hands could be justified. But I think mostly we skip over that part and just notice whether these actions are effective, which feeds the argument that the ends justifying the means. Today they were effective, but that’s just no way to run a country.

Donald Trump has said he would approve the pipeline, though changing this decision will be difficult. With so much investment already made, this is certainly not the end of it.

Leave a Reply