Previous post

Last week I wrote about the left’s abduction of Alexander Hamilton for their own purposes and the use of the popular Hamilton musical to appropriate Hamilton’s brilliance for their political goals. I then realized that part of the problem is that people just don’t understand Hamilton; they don’t understand his economic policies or the sheer inspired genius of his economic policies. If they did, they would never have succeeded in their attempts to appropriate him for liberal causes, so I turn back to Forrest McDonald’s excellent biography for insight.

It is true that Hamilton believed that no person should have hereditary power, privilege, or status, and that all government officials should be chosen “by the people, or a process of election originating with the people.”

It is true that Hamilton believed that no person should have hereditary power, privilege, or status, and that all government officials should be chosen “by the people, or a process of election originating with the people.”

Hamilton was consistent about his disdain for corruption, and I think he would abhor the type of corruption that led to political dynasties like the Kennedys or the Clintons or even the Bushes of today. As I mentioned in my previous post, the great nation was Hamilton’s ultimate goal, and “stability and permanency” was needed in order to accomplish that goal.

Popular perception might lead us to believe that Hamilton was a social justice warrior, but from reading McDonald’s biography, we realize that he believed in the natural balance that would restore justice as long as the nation’s leaders were moral and chosen by the free people. It’s not that he didn’t recognize that inequalities existed, but he believed that these natural tendencies could be harnessed and channeled, rather than compelled into a forced “equality”

A central part of the plan was based upon Hamilton’s sociological perception. As indicated, he observed that natural inequalities among men would give rise to unequal distribution of wealth in any free society in which industry was encouraged (not in every society, just in those so defined). This was already true of the United States despite the country’s newness and abundance of vacant land, and the inequality would increase with time. The rich and the poor, the few and the many, he added, were natural antagonists. If all power were given to the few, they would oppress the many; if all power were given to the many, they would oppress the few.

In other words, Hamilton was an ardent supporter of the republican form of government; it was vital to him that the national government be republican and represented the people as a whole, rather than just the rich. He recognized that income inequality existed, but he opposed redistributing said income for a forced idea of equal distribution of wealth. Instead, he sought a balance of powers, which he believed would ensure that people of all means would have a stake. Each branch of government would represent each class of people. I have to admit, Hamilton had a cunning, if naive, view of human nature and crafted his plan to ensure that all were represented and all had a vested interest in ensuring the nation ran smoothly.

He would institutionalize class struggle, as it were, by vesting each, the few and the many, with a separate branch of government. Neither would dare neglect to participate actively in affairs of the nation, lest its natural enemy gain exclusive control.

Again, Hamilton believed that the natural balance of things would be restored by a) the nature of the people with b) some guidance and manipulation from those who built the nation. Those who would try to appropriate Hamilton as their own would argue that what Hamilton was actually striving for is a widespread ownership of assets, but having read his article in the New York Municipal Gazette, where he wrote for the anti-assessment committee, “Whenever a discretionary power is lodged in any set of men over the property of their neighbors, they will abuse it,” Hamilton was actually arguing against the arbitrary system of assessments.

Do we imagine that our assessments opperate equally? Nothing can be more contrary to the fact. Wherever a discretionary power is lodged in any set of men over the property of their neighbours, they will abuse it. Their passions, prejudices, partialities, dislikes, will have the principal lead in measuring the abilities of those over whom their power extends; and assessors will ever be a set of petty tyrants, too unskilful, if honest, to be possessed of so delicate a trust, and too seldom honest to give them the excuse of want of skill. The genius of liberty reprobates every thing arbitrary or discretionary in taxation. It exacts that every man by a definite and general rule should know what proportion of his property the state demands. Whatever liberty we may boast in theory, it cannot exist in fact, while assessments continue. The admission of them among us is a new proof, how often human conduct reconciles the most glaring opposites; in the present case the most vicious practice of despotic governments, with the freest constitutions and the greatest love of liberty.

What Hamilton was arguing against was progressive taxation – something that liberals today shriek about regularly, claiming that the rich need to pay more than they already do. In addition, Hamilton wasn’t a fan of taxes levied on persons by the federal government. McDonald writes that those taxes were “the most onerous, least productive, and most difficult to collect.” Hamilton preferred that direct taxes on individuals be the sole province of state governments, which is not exactly something today’s left would appreciate, especially since Hamilton opposed raising taxes so high so as to “discourage industry by engendering despair.” The proglodyte supporters of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders certainly wouldn’t appreciate Hamilton’s contention that excessive tax burdens on the producers would essentially result in them no longer having any interest in producing.

What Hamilton was arguing against was progressive taxation – something that liberals today shriek about regularly, claiming that the rich need to pay more than they already do. In addition, Hamilton wasn’t a fan of taxes levied on persons by the federal government. McDonald writes that those taxes were “the most onerous, least productive, and most difficult to collect.” Hamilton preferred that direct taxes on individuals be the sole province of state governments, which is not exactly something today’s left would appreciate, especially since Hamilton opposed raising taxes so high so as to “discourage industry by engendering despair.” The proglodyte supporters of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders certainly wouldn’t appreciate Hamilton’s contention that excessive tax burdens on the producers would essentially result in them no longer having any interest in producing.

In order to know Alexander Hamilton, we need to delve into his thinking, into the writings of Hume, Bacon, Locke, Demosthenes, and others. Hamilton wasn’t a cardboard cutout. His thinking and political philosophies evolved and built upon one another over time – all with the singular goal of creating our great nation.

He also studied writers, both practical and theoretical, who might offer insights into the problems besettling the American cause. In immediate practical terms, the most pressing problem was the financial one of supplying the army; and to inform himself on matters economic and financial Hamilton studied, besides Postlethwayt, Wyndham Beawes’s Lex Mercatoria, Richard Price’s recent treatise on Schemes for raising Money by Public Loans, and possibly Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. In broader terms the problems were governmental, and here Hamilton’s master was David Hume.

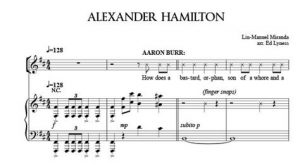

Hamilton wasn’t as simple as a musical and wasn’t as black and white as the left would have us believe. He was a complex individual, who really did voraciously study “every treatise on the shelf,” as the opening number of the musical describes.

Hamilton wasn’t as simple as a musical and wasn’t as black and white as the left would have us believe. He was a complex individual, who really did voraciously study “every treatise on the shelf,” as the opening number of the musical describes.

This is where McDonald’s biography really excels. It doesn’t simply feed us a cool story about one of America’s founding fathers. It opens up his mind and his thinking for us to examine, and when we do so, the brilliant musical simply doesn’t do Hamilton justice.

“He was a complex individual, who really did voraciously study “every treatise on the shelf,” as the opening number of the musical describes.”… Well Hell, that right there proves he’s not a liberal!! they won’t study anything that conflicts with their worldview..

Wherever a discretionary power is lodged in any set of men over the property of their neighbours, they will abuse it.

Hamilton wasn’t a fan of taxes levied on persons by the federal government.

Which is why our Constitution did NOT give the power to tax the people to the then-federal gov’t.

It took 1 1/4 centuries for the states to give up that portion of their sovereignty.

Repeal of the 16th and 17th Amendments is key if we ever want to return to a true “United States” instead of a single behemoth in DC.

But he was a LIIIIIIIIBERAL!

3 Comments